By

Manoblanca - “Manoblanca” and “El romántico fulero” (White Hand and The Ugly Romantic)

hen tango leaves the outskirts to make itself known downtown, a flirt with theater begins. Theater plays were staged in very few theaters and lyrical shows were even more restricted.

Popular audiences were accustomed to an easy sentimental mood and the instruments were the sainete (one-act farce) and the primitive musical comedy, that comprised the so-called «género chicoK. For a small fee some companies used to present up to three little plays a day. But very few were those which had recognition and stayed a long time in vogue, most them did not hold a month. The public greedy for entertainment had to be fed.

Popular audiences were accustomed to an easy sentimental mood and the instruments were the sainete (one-act farce) and the primitive musical comedy, that comprised the so-called «género chicoK. For a small fee some companies used to present up to three little plays a day. But very few were those which had recognition and stayed a long time in vogue, most them did not hold a month. The public greedy for entertainment had to be fed.

Their plots were in the mood of a humorous romantic comedy, sometimes with a little touch of drama and especially with music and, in this was included tango.

The outstanding theaters had their staff orchestras with their corresponding leaders, composers and authors, who were overwhelmed with work. That task meant not only the creation of simple stories but also the lyrics for the new tangos, many times in association with the musicians of those aggregations.

Such was the case of the author Carlos Schaeffer Gallo and the pianist Antonio De Bassi. The coincidence took place at the musical revue Copamos la banca of the above mentioned Schaeffer Gallo with the collaboration in the script by Antonio Botta. The opening was on November 8, 1924 at the disappeared Teatro Ideal on Paraná 426. The play was comprised by several acts and one of them was titled Los románticos fuleros (The ugly romantic ones) in which a tango with the same title, but in singular, was performed:

I

Manyeme que'l bacán no la embroca,

parleme que'l botón no la juna

y en la noche que pinta la luna

la punga de un beso le tiró en la boca.

Aquí estoy en la calle desierta

como un gil pa’ mirar su hermosura

campaneando que me abra la puerta

pa' darle a escondidas un beso de amor.

II

Se lo juro que no hablo al cohete

y que le pongo pa'usté cacho e cielo

un cotorro que ni Marcelo

lo tiene puesto con más firulete.

Si usté quiere la pianto ahora

si usté lo quiere digamelo,

será mi piba mi nena la aurora,

en esta sombra que'n el alma cayó.

I bis

Le pondré garçonnière a la gurda

y tendrá vuaturé limusine,

y la noche que nos cache curda

veremos al chorro Tom Mix en el cine.

Berretín que me das esperanza

metejón que proteje la noche,

piantaremos en auto o en coche

como unos punguistas que fanan amor.

We have to point out that in this lyric there is an interesting handling of lunfardo that anticipates later lyrics which with a much rougher language were, for mi taste, exaggeratedly praised by the specialists.

In this tango piece very interesting allusions to characters of the epoch are made. It mentions Marcelo who was no less than Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear, president of the Argentine Republic, a man of fortune, elegant and aristocratic. As well the cowboy Tom Mix, famous for his motion pictures, is highlighted. Its script essentially narrates the intent of «winning» a woman by offering her the best promises. The combination of this plus a charming catchy melody with a sort of melancholic aura produced a tango that became an immediate boom. Francisco Canaro recorded it as an instrumental in 1924 and again in 1926 but with Azucena Maizani on vocals singing the whole lyrics. After this remarkable presentation the piece was forgotten.

But this did not end here, its composer Antonio De Bassi nearly twenty years later, who knows why, rightly decided to suggest Homero Manzi that he should write a new lyrics to fit its melody. So in 1941 “Manoblanca” was born which, even though without a great number of renditions, has turned out a classic.

Hearing it may make us shiver, because Manzi further added hints of the reality of those years —a generation had passed— but he wisely uses his abilities as romantic poet placing the character on streets and circumstances familiar to us. He tells us the story of a «worker» who finds the time to visit the woman he loves. It is a simple display of neatness, nostalgia and love.

Manzi places the protagonist as living in the neighborhood of El Once and he does not extol the figure of the little carter but his pride for his work vehicle, the cart for carrying loads, the cart with striking colors, the initials, surely surrounded by a fillet and the shining bronze star adhered to the leather sole. At the sixth stanza he confirms it when he says: «el orgullo de ser bien querido» (the proud of being well loved).

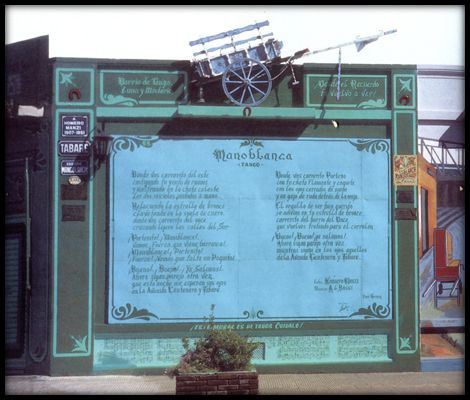

Manoblanca

Dónde vas carrerito del este

castigando tu yunta de ruanos,

y mostrando en la chata celeste

las dos iniciales pintadas a mano.

Reluciendo la estrella de bronce

claveteada en la suela de cuero,

dónde vas carrerito del Once,

cruzando ligero las calles del Sur.

¡Porteñito!... ¡Manoblanca!...

¡Vamos, fuerza, que viene barranca!

¡Manoblanca!... ¡Porteñito!...

¡Fuerza, vamos, que falta un poquito!

¡Bueno! ¡bueno!... ¡Ya salimos!...

Ahora sigan parejo otra vez,

que esta noche me esperan sus ojos

en la Avenida Centenera y Tabaré.

Dónde vas carrerito porteño

con tu chata flamante y coqueta,

con los ojos cerrados de sueño

y un gajo de ruda detrás de la oreja.

El orgullo de ser bien querido

se adivina en tu estrella de bronce,

carrerito del barrio del Once

que vuelves trotando para el corralón.

¡Bueno! ¡bueno!... ¡Ya salimos!...

Ahora sigan parejo otra vez

mientras sueño en los ojos aquellos

de la Avenida Centenera y Tabaré.

Later he describes the man with «the rue leaf on his ear». According to the old saying it brought good luck, what he possibly needed after the end of his labor, to meet with «her eyes» around the corner of Centenera and Tabaré.

In his later tango “Sur” he does not reveal to us the true name of the character but he provides very good hints to discover him. In fact, when he mentions «la esquina del herrero, barro y pampa» (the corner of the blacksmith, mud and pampa) he alludes to childhood memories, precisely the Antonio Salustiano Musladino's blacksmith's shop located on Centenera Street, between Cóndor and Tabaré. His son Oscar, a close friend of the poet's, is the carter, object of his homage in “Manoblanca”.

Two words about Centenera and Tabaré streets. The former is in the memory of don Martín Barco de Centenera, priest and politician born in Spain in 1544. He was at the second foundation of the city of Buenos Aires made by Juan de Garay in June 1580. Back in Spain in 1602, he lived for a time in Lisbon and there he wrote his poem: Argentina y conquista del Río de la Plata con otros acaecimientos de los reynos del Perú, Tucumán y estado del Brasil. He was the first to use the name of Argentina to designate our present territory. Tabaré street, before 1919 was called Oeste. It alludes to the title of an epic-lyrical poem of the Uruguayan poet Juan Zorrilla de San Martín, published in Montevideo in 1888. In it he narrates the story of an Indian, son of the charrúa chief Caracé and of a Spanish white woman that was captive. The critics regard it as a unique poem of its kind, which has been revered and taken into account through the times.

Recordings of “El romántico fulero”:

Francisco Canaro Orchestra, singing Azucena Maizani (1926)

Walter Yonsky, with guitar by Bartolome Palermo y Paco Peñalva (1998)

Recordings of “Manoblanca”:

Alberto Castillo, with his orchestra Dir: Emilio Balcarce (1943).

Ángel D'agostino Orchestra, singing Ángel Vargas (1944)

Nelly Omar, with guitar by José Canet.

Carlos Souza, with Armando Lacava Orchestra.

Alberto Castillo, with Osvaldo Requena Orchestra (1976).

Cedrón Quartet, instrumental (1978).

César Consi, with guitar by Consi, Ferreira, Fontela y Palacios (1985).

Rubén Llaneza, with guitar by Alberto Remersaro (1994).

Walter Yonsky, with guitar by Bartolome Palermo y Paco Peñalva (1998).

Ricardo Bonaventura, with gutitar by Jorge Nimo (1999).