By

Tango in Poland, 1913 - 1939

agree with a theory that our liking, taste and predilection are rooted in our childhood and arise from what we had lived on. However, the older I am, the more aware I become that there must be still one condition fulfilled: the child we refer to must have particular inclination and sensitivity of his own before absorption occurs. And I think that it was my case.

When I was 4 or 5 years old I was able to distinguish by ear for instance the voice of Beniamino Gigli from the voice of Tito Schipa. My favourite toys were old gramophone records and archive photos. My beloved fairy-tales were stories about Bohemian life witnessed by my parents in their early youth. Such a world was surrounding me and it might have had no impact, if I were not attracted to it.

When I was 4 or 5 years old I was able to distinguish by ear for instance the voice of Beniamino Gigli from the voice of Tito Schipa. My favourite toys were old gramophone records and archive photos. My beloved fairy-tales were stories about Bohemian life witnessed by my parents in their early youth. Such a world was surrounding me and it might have had no impact, if I were not attracted to it.

Especially, gramophone records had for me something mysterious in their nature: strange labels, different than any other picture, in the middle of a black disc. The disc, when turned around, started to emit the sound: Chopin’s preludes, Tschaikovsky’s waltzes, an early American swing or most famous Argentine compositions of Rodríguez and Ángel Villoldo were coming out from under the iron needle. Now, when I try to recollect that experience, I am sure that melodies which at my home were most frequently sang, hummed or crooned by my parents, were Polish tangos. No wonder, popular melodies in the so-called «between wars time» in Poland were compositions conceived just in the rhythm of tango.

Tango emerged in Poland soon before outbreak of the World War I. Ludwik Sempolinski, an artist and historian, in his memoirs records the fact that in the «latest operetta by Jacoby which was put on the stage in Warsaw on October 28th 1913, a new dance Tango was introduced and was performed by Lucyna Messal and Jozef Redo».

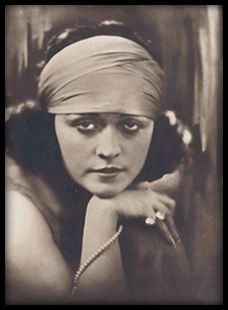

In my collection, there is a unique sheet music, Aime Lachaume’s composition, “Regina-Tango”,edition 1913, Warsaw. On the front page under the title, there is a photo of Pola Negri together with her partner, Edward Kuryllo, in a tango-like embrace. Pola Negri, dancer in Warsaw, at that time 17 years old, could not have yet dreamed of the fantastic future that was in store for her in the international film production. I think that it may be noted here, that 25 years later, Pola Negri was singing “Tango Notturno” in one of her last sound pictures; an interpretation that, in my opinion, is beyond anything of the kind created in Europe in that decade.

In my collection, there is a unique sheet music, Aime Lachaume’s composition, “Regina-Tango”,edition 1913, Warsaw. On the front page under the title, there is a photo of Pola Negri together with her partner, Edward Kuryllo, in a tango-like embrace. Pola Negri, dancer in Warsaw, at that time 17 years old, could not have yet dreamed of the fantastic future that was in store for her in the international film production. I think that it may be noted here, that 25 years later, Pola Negri was singing “Tango Notturno” in one of her last sound pictures; an interpretation that, in my opinion, is beyond anything of the kind created in Europe in that decade.

In 1919, an actor, Karol Hanusz is singing “The Last Tango” in a Warsaw cabaret Black Cat, music by E. Deloire and lyrics starting with the words: «Under the blue sky of Argentina...»

In 1922, a singer, Stanislaw Ratold records on a Beka Grand Record, a Polish version of “Tango du reve”, music by E. Malderen.

Until the mid-twenties, tango in Poland shared its position with other fashionable dancing rhythms: one-step, shimmy, fox-trot and waltz. I think that something exceptional happened soon after 1925 when Zygmunt Wiehler composed the tango “Nie dzis to jutro” (If not today, tomorrow will do) for Hanka Ordonowna, our prominent singer and actress, a star of Qui pro Quo cabaret.

Until the mid-twenties, tango in Poland shared its position with other fashionable dancing rhythms: one-step, shimmy, fox-trot and waltz. I think that something exceptional happened soon after 1925 when Zygmunt Wiehler composed the tango “Nie dzis to jutro” (If not today, tomorrow will do) for Hanka Ordonowna, our prominent singer and actress, a star of Qui pro Quo cabaret.

From that moment on tangos in Poland, as a home production, were coming down in streams. The hit of the year 1928 was the tango “Wanda”, the story of a Polish girl sold out to a cheap pub in Argentina where nobody cares about her except a guitar player who promises her a better life somewhere else, if she only agrees to go away with him.

All those Polish tangos of the late twenties were to some extent copies of a true Argentine style. The most cherished performer of that genre was Stanislawa Nowicka, soon even called a Queen of Tango. The stories revealed in those songs usually had much the same motives: complaints of a poor girl, absolutely devoted to her ruthless lover, a master of a night and knife: «Tonight you will beat me again until I die of screaming / But I have no strength to go away from you, you lousy bastard!»

The year 1929 was a climax: Jerzy Petersburski composed his “Tango Milonga” which, with German and English lyrics as “Oh, Donna Clara”, immediately dominated other hits throughout the world. In the same year, Wladyslaw Dan, a young musician, decided to prepare in Warsaw an evening of tangos sung in Spanish language by a group of five young gentlemen with guitars, accordion and piano. The show was opened with “Plegaria” by Eduardo Bianco and closed with “Mamita mía” by Enrique Delfino. Wladyslaw Dan ventured to make an experiment: he himself composed for this evening two tangos in Argentine style with lyrics especially written in Spanish. Their titles were: “Siempre querida” and “Liana”. The vocal group was named for that performance: Coro Argentino V. Dano, later known as Chor Dana.

The fashion for tango in Poland was brought from the west. Nevertheless, it should be noted that Warsaw, opposite to Paris, Madrid or Berlin was not the aim of travelling groups of Argentine musicians and singers. Tango came to Poland through gramophone records, newspapers' rumours and radio. Poland was only well prepared to welcome it, as there had always been a sort of hunger for exotic novelties.

The fashion for tango in Poland was brought from the west. Nevertheless, it should be noted that Warsaw, opposite to Paris, Madrid or Berlin was not the aim of travelling groups of Argentine musicians and singers. Tango came to Poland through gramophone records, newspapers' rumours and radio. Poland was only well prepared to welcome it, as there had always been a sort of hunger for exotic novelties.

Some original Argentine tangos gained unparalleled popularity and were immediately performed and recorded in Polish versions. Yet, the authors of Polish lyrics did not bother at all about the contents of the original text. They used to write their own combination of plots in a Spanish-like or South American or mixed together style with props typical for those countries.

For instance: “Mama yo quiero un novio” had Polish title “Santa Madonna”; “Adiós muchachos” was transferred to “Donna e Caballeros”; “Sonsa” existed in Polish version as “Concha”; chorus of “Yira yira” started with an imperative “You must do it!”. Extremely popular, mentioned above, “Adiós muchachos” had even two different versions in Polish language.

The year 1930 and a hit “Juz nigdy” by J. Petersburski brought a new air into Polish tango:

Never more - will I hear you speak the words of love,

Never more - will I press you to my hungry lips,

You've gone away,

How am I to take it that you will not return

day or night, thought or dream,

Never more!

Tango became a sort of sentimental expression with a melancholic and even depressive air. Such were threads of lyrics but music, apparently, was following those texts in their mood. The refrains had something what may be called a «heart-breaking» essence and that was what made them, I think, so popular. And popularity resulted —as usual— in an increasing demand for new items of the kind.

With every passing year, features of Polish tango had less and less in common with the Argentine prototype. The more tangos were composed as a home product, the lesser was interest for overseas production. Polish tango's rhythmical base was delicate and usually slow. The orchestration was kept rather in the shade of the first voice, the haunting melody:

This is the last Sunday,

today we shall part with each other,

today we shall go away from each other,

for the rest of our life.

This is the last Sunday,

so don't stint it to me,

look tenderly at me,

for it's the last time.

In other words mood of yearning and nostalgia was on the foreground in tangos created by Polish composers. Their names Jerzy Petersburski, Zygmunt Karasinski, Artur Gold, Zygmunt Bialostocki, Fanny Gordon, Henryk Wars, Michal Ferszko, to mention a few.

Still, there were two musicians: Arcadi Flato, arranger of the Odeon studio orchestra and Henryk Gold, arranger for Columbia, who tried, with success, to keep Polish tangos be vivid, with sharp accents and the typical Argentine spicy character.

Lyricists remained in a shade of Andrzej Wlast, who may be called a champion, as far as a number of texts, written by him, are concerned. Our poets Julian Tuwim and Marian Hemar happened to write some beautiful lyrics for tangos, too.

Lyricists remained in a shade of Andrzej Wlast, who may be called a champion, as far as a number of texts, written by him, are concerned. Our poets Julian Tuwim and Marian Hemar happened to write some beautiful lyrics for tangos, too.

I think that it is worth mentioning that most of those composers and lyricists, born in Poland and educated as Polish artists, actually were of Jewish origin and had a burden of a Russian occupation and influence of many years. These circumstances may account to some extent for their artistic choices and predilection to nostalgic keys in their music.

In the mid-thirties our phenomenon might have already been called Polish tango. I think that no other country of Europe became such an object of tango-fever as Poland. In my searches, whenever I happen to find, for instance, 5 old Polish records, 4 of them are always with tangos. The last page of every sheet music, where novelties are advertised will show us that more than 3/4 of all popular songs in Poland were tangos. The same may be evidenced when looking through the catalogues of gramophone records.

A few days before the outbreak of World War II, Janusz Poplawski, a tenor singer, recorded at the Warsaw Odeon studio the tango “Zlociste chryzantemy”, which, in some way, closes in Poland the epoch of great musical adventure:

Golden chrysanthemums, in a crystal vase

are standing on my piano,

soothing sorrow and regret.

Through the silvery and misty tears

I reach out my hands to them

and whisper one question:

why have you gone away?