By

Cambalache - «...and in 2000 too!», “Cambalache” and the censored lyrics

n 1936, the international enterprise SOFINA was allowed to extend the concession deadline granted to its branch CHADE —Hispano-Argentine Electricity Company— (later CADE) for the supply of electricity in Argentina with the complicity of the President Agustín P. Justo’s government and by means of bribery to the Radical Party and its councilors.

The Radical Party used that benefice to finance the campaign to elect Marcelo T. de Alvear and to build the Casa Radical, a monument to honor corruption.

The Radical Party used that benefice to finance the campaign to elect Marcelo T. de Alvear and to build the Casa Radical, a monument to honor corruption.

About that bribery, president Justo expressed «it is the first case of a political party that is corrupted being in the opposition».

This shady deal was analyzed in the Cuadernos published by the FORJA group, whose members interrupted the Radical meetings with an anti-personalist majority by shouting «CADE, CADE».

In 1944, the de facto president Pedro P. Ramírez ordered an investigation of the affaire appointing a commission headed by Colonel Matías Rodríguez Conde and comprised by Juan Pablo Oliver and Juan Sabato. It wrote a report that demonstrated that those briberies had existed.

The copies of the Rodríguez Conde’s report were sequestered and later burned on Colonel Juan D. Perón’s orders in return for the contribution made by the CADE in his electoral campaign. Perón coined the slanderous qualifying term cadista with which he, paradoxically, abused his opponents of the Unión Democrática.

Sixty-four years later a scandal takes place again when the Senators were bribed in order to pass a law that had been worked out by another coalition government to change labor conditions.

There are some differences between both cases of corruption: in the first, the briber was a private company; in the second, suspicions point to the government as guilty of misfeasance in office. Those who were bribed in 1936 belonged to the same party; in the year 2000 opponents and, at least, one follower of the government’s policies had their hands dirty.

At the present case that expression used by Justo cannot be applied: the today’s opposing party was already corrupted when it was the official party.

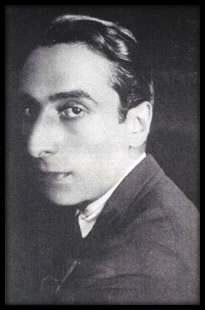

How keen was Enrique Santos Discépolo’s vision when he prophesied «that the world was and will be like junk, I already know…In five hundred and six, …and in two thousand too!»

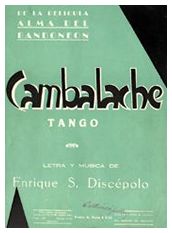

“Cambalache” had the peculiar privilege of being banned by all the military dictatorships from 1943 on. Its lyrics, a witty accusation of corruption and impunity in the «década infame» (despicable decade), is in force today as it was in 1935.

“Cambalache” had the peculiar privilege of being banned by all the military dictatorships from 1943 on. Its lyrics, a witty accusation of corruption and impunity in the «década infame» (despicable decade), is in force today as it was in 1935.

It was written in 1934 for the film El alma del bandoneón, which was premiered in February 1935 and whose lead actress was Libertad Lamarque. The tango is sung by Ernesto Famá with the accompaniment of the Francisco Lomuto’s orchestra. This motion picture is the first of a cycle in which the actress and singer, impersonates a series of characters punished by the system in movies that dealt with a social problem.

The neutrality favorable to the countries of the Axis kept by President Ramón Castillo in 1943 prohibited that the film El fin de la noche was shown. It also starred Libertad Lamarque and the lead actor Juan José Míguez and was directed by Alberto de Zavalía. The setting was a nation invaded by the Nazis and in it Libertad was showcased performing the tango “Uno”. That movie was finally premiered after the coup that took place on June 4.

Discépolo’s tangos underwent the consequences of the naive morals imposed by that uprising. The minister of Education, Gustavo Martínez Zuviría (Hugo Wast), formed a commission headed by Monsignor Gustavo Franceschi in order to protect the purity of the language. Then it charged against tango pieces and prohibited voseo (addressing with the familiar form of vos as a substitute for tú) and the use of lunfardo terms.

The authors of the banned tangos had to change all of a sudden the «offensive» terms to adapt them to the bigotry of those purists. It resulted in titles and words that, for being ridiculous, altered the sense of the lyrics which finally became a parody of tango.

In 1949, Discépolo and other authors went to see President Juan D. Perón whom they persuaded that that ban damaged their labor sources. So they achieved the derogation of that arbitrary measure.

In 1949, Discépolo and other authors went to see President Juan D. Perón whom they persuaded that that ban damaged their labor sources. So they achieved the derogation of that arbitrary measure.

The relationship between Discépolo and Perón originated the radio program I think and I say what I think on which the minstrel of the Buenos Aires streets —as accurately Norberto Galasso called him— had a dialogue with Mordisquito, an imaginary opponent to the government. It turned out an extraordinary radio hit. Perón said that his re-election on the November 11, 1951 elections was due to women's vote and to Mordisquito.

As a consequence of his voluntary and unconditional adhesion to Perón, Discépolo was hated and despised by the artists who were opponents to the régime.

Francisco García Jiménez and Anselmo Aieta were luckier. They, soon after the military coup of September 6, 1930, as a servile reverence, composed the tango “Viva la patria”, a padded flattery fortunately (for its authors) forgotten by the public.