By

Mi noche triste - “Mi noche triste”, the "tango-canción"

nder this title it entered the history of tango song and, if for any reader this statement turns up contradictory, we have to accept that after so many years, this definition was settled for most authors.

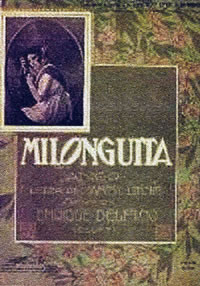

As in the case of many creations it was by chance. The musician had a passive attitude. The author of the lyric, used a melody already composed which had another title and, not on purpose, opened the door for a long trip, with unimaginable consequences for him and for the musician. The argument began because for some people the beginning of tango song is as from “Milonguita”. They think the core of the issue is in the joint will of making a music and a lyric, a purpose that reunited Enrique Delfino with Samuel Linnig. This is a sibylline argument. Who cares if it was an event that took place by chance, individually carried out or planned by both authors?

As in the case of many creations it was by chance. The musician had a passive attitude. The author of the lyric, used a melody already composed which had another title and, not on purpose, opened the door for a long trip, with unimaginable consequences for him and for the musician. The argument began because for some people the beginning of tango song is as from “Milonguita”. They think the core of the issue is in the joint will of making a music and a lyric, a purpose that reunited Enrique Delfino with Samuel Linnig. This is a sibylline argument. Who cares if it was an event that took place by chance, individually carried out or planned by both authors?

Furthermore, “Milonguita” was released in 1920, four years had already passed and the melody and the lyrics of “Mi noche triste” were already deep in the people’s hearts. Especially, those phrases were soon incorporated to the daily language: “Percanta que me amuraste en lo mejor de mi vida” or “siempre llevo bizcochitos pa´tomar con matecitos...” or “la guitarra en el ropero” and the formidable lines that define, as no other, the heartbreak for a lost love: “Y si vieras la catrera, como se pone cabrera cuando no nos ve a los dos”.

For the first time a tango tells us a complete story, with beginning, development and end. It’s implied that previously there were tangos with lyrics, but on a very simple and different structure, which described the profile of some character, most of the times in a jolly mood: “La morocha”, “Don Juan”, “El porteñito”, etc.

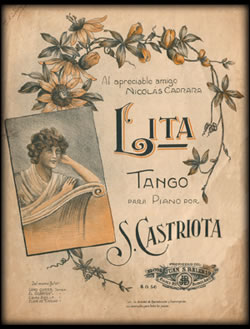

In Buenos Aires, a trio lined up by Samuel Castriota on piano, Antonio Gutman on bandoneon and the violinist Atilio Lombardo used to play at the café El Protegido on the corner of San Juan and Pasco. During 1916, Castriota had premiered a new number: “Lita” published by Juan Balerio and dedicated to Mr. Nicolás Caprara.

On the other bank of the River Plate at the cabaret Moulin Rouge of Montevideo located on the upper floor of the Teatro Artigas, owned by Emilio Mattos who was the father of the composer of “La cumparsita”, Pascual Contursi was singing with his guitar. The newspaper “El Día” on March 22, 1916 published the following news: «We had the chance of hearing the young criollo singer Pascual Contursi performing pieces requested by the audience. His songbook includes many of the songs of the Gardel-Razzano duo and a lot of numbers to which he added his own lyrics...» Some days later the same paper highlighted the success achieved by the lyrics he added to the tango “El flete” composed by Vicente Greco.

On the other bank of the River Plate at the cabaret Moulin Rouge of Montevideo located on the upper floor of the Teatro Artigas, owned by Emilio Mattos who was the father of the composer of “La cumparsita”, Pascual Contursi was singing with his guitar. The newspaper “El Día” on March 22, 1916 published the following news: «We had the chance of hearing the young criollo singer Pascual Contursi performing pieces requested by the audience. His songbook includes many of the songs of the Gardel-Razzano duo and a lot of numbers to which he added his own lyrics...» Some days later the same paper highlighted the success achieved by the lyrics he added to the tango “El flete” composed by Vicente Greco.

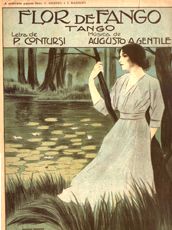

He had already begun to look after other people’s melodies so that his lyrics, with some changes, would fit to them. One of his early attempts was with Augusto Berto’s piece: “La biblioteca”, which by then was also known as “Son las doce y van cayendo”. Other lines of his found the adequate melody in Arolas’ “La guitarrita”, renamed as “Qué querés con esa cara”. Also with Manuel Aróztegui’s “Champagne tangó”, which was dedicated to the actor Florencio Parravicini, and Augusto Gentile’s “El desalojo”, which with lyrics became “Flor de fango”. And suddenly a miracle occurred, a smash hit, the boom, our tango at issue.

No doubt, the first to sing it was Contursi himself at the Moulin Rouge. The Uruguayan lyricist Víctor Soliño has another version. In an interview in 1969, he said that at the time of the creation Gardel and Razzano were performing at the Teatro Urquiza of Montevideo and it was then when they premiered “Mi noche triste”. And that they later brought it back to Buenos Aires. Other notes in journals said, instead, that only Razzano was in Montevideo.

It is very interesting what Dr. Luis Adolfo Sierra says about it, in a communication to the Academia Porteña del Lunfardo. Sierra had written to José María Contursi to ask him some questions about Pascual, his father. In a paragraph of the answer "Katunga" told him: «Some months after his death, I met Gardel at the tearoom Las Violetas on Rivadavia and Medrano... and he told me: "Poor your Dad!, you know that we were friends of the dancehalls. For some years I had not seen Pascual because he loved Montevideo, but one day he turned up around here and told me, after borrowing me the guitar: "-I'm gonna make you hear a tango". I was struck, a tango? He said it belonged to an Uruguayan boy who passed it to me at the Royal. I liked it so much that I learned it soon. I sang it for my friends who enjoyed it, but I did not dare to sing it in public, until the day I, a bit afraid, did it at the Esmeralda (now Teatro Maipo). It was a hit and then I knew that Pascual was the author...»

It is very interesting what Dr. Luis Adolfo Sierra says about it, in a communication to the Academia Porteña del Lunfardo. Sierra had written to José María Contursi to ask him some questions about Pascual, his father. In a paragraph of the answer "Katunga" told him: «Some months after his death, I met Gardel at the tearoom Las Violetas on Rivadavia and Medrano... and he told me: "Poor your Dad!, you know that we were friends of the dancehalls. For some years I had not seen Pascual because he loved Montevideo, but one day he turned up around here and told me, after borrowing me the guitar: "-I'm gonna make you hear a tango". I was struck, a tango? He said it belonged to an Uruguayan boy who passed it to me at the Royal. I liked it so much that I learned it soon. I sang it for my friends who enjoyed it, but I did not dare to sing it in public, until the day I, a bit afraid, did it at the Esmeralda (now Teatro Maipo). It was a hit and then I knew that Pascual was the author...»

The recording for the Nacional-Odeon label was on April 9, 1917. As for the widely spread information that Gardel had recorded first "Flor de fango" but that, for some reason, only was released for sale two years later, Sierra, after a series of explanations too technical for this essay, contradicted that belief and affirmed that "Flor de fango" was recorded 2 years later and at the time of the release.

With a difference of a few days, in that same month and year, the Roberto Firpo Orchestra recorded "Mi noche triste" as an instrumental (disc Odeon 574) and Francisco Canaro, on September 6, 1918 recorded under the same title, a waltz with the following addenda, «Sobre motivos del tango de Samuel Castriota».

Before the premiere in Buenos Aires there was a clash between the authors. It was because of the title "Lita" which was immediately set aside because it had no meaning altogether. Contursi suggested "Percanta que me amuraste", which in no way the elegant Castriota accepted. But the intervention of Gardel and Razzano settled the misunderstanding and suggested the one which finally remained. For some reason the author filed in the record its lyric in June 1917, without indication if it was a tango or simply a poem, under the title "Mal de ausencia".

Before the premiere in Buenos Aires there was a clash between the authors. It was because of the title "Lita" which was immediately set aside because it had no meaning altogether. Contursi suggested "Percanta que me amuraste", which in no way the elegant Castriota accepted. But the intervention of Gardel and Razzano settled the misunderstanding and suggested the one which finally remained. For some reason the author filed in the record its lyric in June 1917, without indication if it was a tango or simply a poem, under the title "Mal de ausencia".

When the disc was publicly released it did not received the expected recognition. It remained in a second level, as if awaiting, because when something has to happen, the circumstances appear.

Time later a little theater play was being rehearsed, one of those that lasted a couple of weeks on stage if they were lucky. Its title: "Los dientes del perro", a sainete (one-act farce) by José González Castillo and Alberto Weisbach, played by the Muiño-Alippi company at the Teatro Buenos Aires. The rehearsals did not satisfy Alippi. It was a two-scene play, the first was totally set in a cabaret and something was needed to spice it. Then he thought about including a tango. Gardel, when he knew about it, sang "Mi noche triste" for him and then the enthusiasm was back. One of the actresses performed it. It was Manolita Poli accompanied by the Roberto Firpo's orchestra. They achieved a notable acclaim. Many people went more than once to the theater only to listen to the song again.

Even though there were over 400 performances, again a new problem arose between Castriota and Contursi. The former, a calm man, with a good way of talking and a good temper obtained the 60% of the profits. Contursi, more passionate, the 40%. The poet thought that the success was due to his lyric and he wanted equal shares. He fought tooth and nail at the Odeon offices before Max Glücksmann that Castriota lost his temper and shouted: «But do you think you've written The Lady of the Camellias?» True or not it entered history. The tango was withdrawn from the sainete for the second season. Instead of it "¿Qué has hecho de mi cariño?" appeared. It had the melody of "Royal Pigall" composed by Juan Maglio to which José González Castillo added lyrics.

The success was due to the tango or the play? O maybe was it due to the scene at the cabaret? A place for wealthy people who aroused the curiosity of most of the people who were unable to afford that. Cabaret was for the "high life" boys, not for common men.

The success was due to the tango or the play? O maybe was it due to the scene at the cabaret? A place for wealthy people who aroused the curiosity of most of the people who were unable to afford that. Cabaret was for the "high life" boys, not for common men.

These little plays, which formed a theater genre called "género chico", were frequented by poor young people, including women employees and housemaids. And these daily performances allowed them entertainment for a pair of coins.

As for the replacement of a tango by another, I'm inclined to think that it happened because of the money problems between the authors.

The tango piece had another theater appearance. It was brief but we have to mention it to highlight its success. It was at the Contursi's and Manuel Romero's sainete "Percanta que me amuraste". At the final scene there is a lamp with low light, the orchestra plays the tango and the lead players appear kissing each other. At that time all the players onstage forming a choir sing: «Y la lámpara del cuarto / también tu ausencia ha sentido / porque su luz no ha querido / mi noche triste alumbrar.» (And the room's lamp / has also felt your absence / because its light has denied / to light my sad night). And the stage curtain went down.

Its lyrics became so popular that soon low-quality humorists using the same melody changed its lines by others frankly obscene: «De noche cuando me acuesto / no puedo taparme el rabo / porque se me para el nabo / al acordarme de vos...» (At night when I go to bed/ I can't cover my ass/ because my prick is turned on/ when I remember you).

The arguments between the authors were not a reason to stop them working together again. So "Sentate hermano" sprang up, with the subtitle "Bebé conmigo". Then it was said that Castriota, when he knew of Pascual's serious state of health –he had gone mad because of syphilis- granted him the percentage of his copyright.

When after the revolution in 1943 the lunfardo language was banned in order to achieve a greater correction of expression for the people all the weight of the ridiculous regulation fell on the city music. We have as an example "Mi noche triste", with its lines modified, in the recording by Florindo Sassone with Jorge Casal on vocals.

After the deaths of Castriota and Contursi, both in 1932, two successive copies of the "Sintonía" magazine of October 1934 say that Príncipe Cubano (Ángel Sánchez Carreño) would file a suit against them for plagiarism because his bambuco "Rosa" had the same melody and lyrics. With this number he had already been awarded the first prize at a contest held at the Salon Magic of Paris in 1914. The chronicle was ill-disposed but had a right assertion, the melody turned out the same, but not the lyrics.

The Cuban had arrived in Buenos Aires as singer and to start a legal action would endanger his future in the country. This would be the reason why he declined to sue. Soon later he would become an important figure of the famous Chantecler cabaret. The trustworthy influential man that received people at the entrance door.

The music was really plagiarized. This was confirmed by Hugo Lamas and Enrique Binda in his book "El tango en la sociedad porteña 1880-1920", in it they also ratify Contursi's authorship but consider his lyrics of little value. But reality shows us that the plot of the lines of "Mi noche triste" were, not only accepted, but also copied immediately and till boredom in hundred of tangos.

There would also be a sociological explanation. Its lyric reflects the loneliness of man in a city without women. Buenos Aires was flooded by immigrants, mostly men, the scarcity of women forced men to only two possibilities of a relationship: at the whorehouses or during a dance at a cheap local, but always paying for that.