By

Hombre de la esquina rosada (Man from the Pink Corner) - Borges and tango

iterary art is normally developed in the bi-dimensional scope of paper and only true writers succeed in transcending into such a third dimension like the hidden message, the visualization of the scene, etc.

Jorge Luis BorgesJorge Luis Borges, our dear Borges, is one of those chosen to be granted talent, to which he added all his work capability in his ever-arduous writings, achieving in each of them a very peculiar poly-dimensionality that goes from his recreation of the language up to the handling of irony to avoid an answer irritating to his modesty.

Jorge Luis BorgesJorge Luis Borges, our dear Borges, is one of those chosen to be granted talent, to which he added all his work capability in his ever-arduous writings, achieving in each of them a very peculiar poly-dimensionality that goes from his recreation of the language up to the handling of irony to avoid an answer irritating to his modesty.

Let us remember, as example of what was said, his so-renowned aversion to tango of which he allowed himself to rescue the merry and frolic ones of the old stream (Ángel Villoldo, Ernesto Ponzio, Vicente Greco, in spite of the fact he did not mention them) and the verses of that ineffable poem Fundación mítica de Buenos Aires (Mythical Foundation of Buenos Aires), in which he describes his love for Buenos Aires.

Who can love so much this city if he does not thoroughly know it?

And who can know it thoroughly without noticing that its paving stones, its squares, its people and its monuments are soaked with the tangos that described it from the late years of the nineteenth century until nowadays?

Let us try then to get to the bottom of that diaphanous mystery that is a Borges that always makes possible as many readings as readers he may have. And let us do it with one of his most perfect stories, that one from which we stole the title to head these lines: Hombre de la esquina rosada.

From the point of view of the detective stories genre all is a literary braggadocio to let us catch a glimpse of the killer from the third paragraph "... More than three times I was not in touch with him, and those on the same night..." but that detail is not enough to measure the stature of the writer: it is a simple sample of "profession".

Intentionally we have used the word "killer" since the author of death cannot be regarded as "murderer": he has no rancour, passion does not guide him, he simply fulfills his duty as executioner, he kills the one who killed his idol. He kills the one who killed his illusions, his miser hopes of social ascent and, even though he simultaneously demonstrated he was able to occupy the place of "guapo" (tough guy) that together with life had lost his referent, he teaches us that it was not either his purpose.

Vaguely he reminds us of that passage in "Silbando" where it is said that almost anonymously "a moan and a deadly shout spring up/ and shining amid the shadow / the sparkling brightness with which a dagger / strikes its fatal stab".

Vaguely he reminds us of that passage in "Silbando" where it is said that almost anonymously "a moan and a deadly shout spring up/ and shining amid the shadow / the sparkling brightness with which a dagger / strikes its fatal stab".

Because of its descriptive qualities, the scenery on which the action takes place deserves a special paragraph: a lonesome plain that due to the night darkness reaches outer space features, stretches out from the Arroyo Maldonado (stream)(today Avenida Juan B. Justo) at its crossroads with Gaona.

A lonesome and ominous red light uncovers the true nature of the large shed where the malandras (bad guys) of the nearby places and the chinas cuarteleras (garrison gals) who recovered themselves in the neighboring huts from the demands of their trade, reunited to dance.

Leaning on the counter, Rosendo Juárez, the master of the place, the summary of all the ideals and hopes that those souls are capable to imagine, the model to imitate, drinks his caña (uncured brandy) with taciturn gesture; it is not the omen of a death he does not imagine, it is simply the aura that prevents the others from asking details of his background, and exempts him from giving them.

There is no happiness in the scene, it cannot exist there; there is hopelessness, there is routine, any laugh is grotesque, a question of "pure nosy Italians", and even the dance is pensive but alert because the attitude is of rivalry.

Where is, then, the happiness of that picaresque tango that sounds in our ears while we read?

What does suggest us of that Borges who tells us that good tango, was the plain, merry, affectionate and playful tango of the beginnings?

Along the unmeasurable pampa-night is coming a town square cart with reddish high wheels. On it, another group of marionettes obeying another puppeteer, are nearing the shed among alcoholic laughters and milongas plucked on the strings of some native guitar.

They do not either come thinking of a night of spree: they know it is a lethal mission, if they were asked they would doubt to be alive some time later; but they are clustered behind their leader, the only one conscious of the expedition's why.

They do not either come thinking of a night of spree: they know it is a lethal mission, if they were asked they would doubt to be alive some time later; but they are clustered behind their leader, the only one conscious of the expedition's why.

Frogs, dogs and crickets complete the scene where the tragedy is to take place and it begins when Real, the other one, launches the challenge without mentioning the addresse; he knows the esprit de corps of the locals will line after the one that is challenged as soon as the latter takes it personally, but he also knows that that same acceptance will be the stopping shout which will turn the suspicious pitched battle into a two-knives tango that will accomplish its ritual up to fatality.

And that is the tango loved by the ironic Borges: it is not playful, it is not joyful, it is tragic, it is lethal.

How many times did the cunning maestro show us his admiration for a knife fight, with all the courage that implies knowing that death is close at hand?

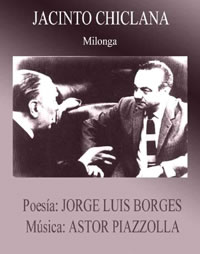

How many times Nicanor Paredes or Jacinto Chiclana?

Isn't this one more time?

The following scene seems to show it is not: Rosendo Juárez, El Pegador, refused the invitation and decided to lose all his estate once and for all: his fame, that one he achieved through hard work or by telling lies but which made everything easy for him, even the possession of that woman who no longer belongs to him since she, out of self pride, takes his knife from his clothes and places it in his hands, ready to be a thing for her man provided he would be the best ("Vayan abriendo cancha, señores, que la llevo dormida!..." Real will say at the time of his triumph, but la Lujanera will have before persuaded him of his submission: "Leave this one alone, he made us think he was a man").

The knife, always the symbolic knife, flies through a window and we wait for the curtain to fall but three actors will continue a script of dramatic overtones that ends with Real dead and debased at the large shed that, soon, will recover the dance so that the staccato bars of tango lead the authorities to accept the innocence of the scene.

On what tangos did Borges cradle this tale?

Disrespectfully I allow myself to think that on some of these that my ears imagined while I read "Tres amigos", in which the narrator is longing for his friends that were "el trío más mentado que pudo haber caminado" (the trio most spoken of that ever existed) and he insults us from his nostalgia by telling us that it is impossible to bring back those days.

Disrespectfully I allow myself to think that on some of these that my ears imagined while I read "Tres amigos", in which the narrator is longing for his friends that were "el trío más mentado que pudo haber caminado" (the trio most spoken of that ever existed) and he insults us from his nostalgia by telling us that it is impossible to bring back those days.

Through all of Borges´s tale there is a background of ownership which, extrapolated to its limits, seems to murmur the word "friendship". And, furthermore, we perceive in the narrator the nostalgia for that other time.

"Culpas ajenas" where Ponzio made his discharge, reminds us of that power of friendship from which it is silently assumed the role a friend left empty, be it with his knife or with his silence.

"El Tigre Millán", in Francisco Real's description, el Corralero, dark hair, tall, stout, with self-confidence.

"Como abrazado a un rencor": Real, when asking to be relieved of the shame of dying seen by the others, is repeating the verse "...I´m neither looking after comfort nor after forgiveness, I neither want sacraments nor funeral words, I surrender myself peacefully as I surrendered myself to the cop...".

But in none of them I can perceive shines of happiness that essentially differentiate those melodically humble tangos by Saborido mentioned in the tale, from the romantic bars by Juan Carlos Cobián, the Chopin-like Osmar Maderna's raptures, the very affectionate Aníbal Troilo's whispers and the schooled tango "fugues" by Piazzolla or Rovira.

But in none of them I can perceive shines of happiness that essentially differentiate those melodically humble tangos by Saborido mentioned in the tale, from the romantic bars by Juan Carlos Cobián, the Chopin-like Osmar Maderna's raptures, the very affectionate Aníbal Troilo's whispers and the schooled tango "fugues" by Piazzolla or Rovira.

All that is tango and its effect in each one of us is perfectly described when Borges tells us "Tango did what it pleased with us and it led us and misled us and it ordered us and found us again".

Before such a definition, let us agree, gentlemen, that Borges is Tango and not only tango.