By

The itinerant singers (payadores) and the early recordings in Buenos Aires

n Buenos Aires the early recordings were made with traveling machines like in Europe and the United States of America. For example, the tenor singer Enrico Caruso made his debut in the world history of recording by standing up in front of a recording horn in March 1902. On that occasion he cut ten waxes for his first ten discs (let us remember that discs were then recorded on only one of their sides).

The event took place on the third floor of the Spatz hotel in Milan. This was after the technicians sent by the small and very humble company Gramophone persuaded the stubborn hotel owner who was against the installation of a recording machine. They succeeded thanks to Humberto Giordano, author of the operas Fedora and Andrea Chenier, who interceded on behalf of that. That hotel used to regularly accommodate musicians and opera celebrities. Four months before, on the second floor, Giuseppe Verdi had died. In like manner, in our city, cylinders and discs were recorded by monologists, musicians and payadores.

The event took place on the third floor of the Spatz hotel in Milan. This was after the technicians sent by the small and very humble company Gramophone persuaded the stubborn hotel owner who was against the installation of a recording machine. They succeeded thanks to Humberto Giordano, author of the operas Fedora and Andrea Chenier, who interceded on behalf of that. That hotel used to regularly accommodate musicians and opera celebrities. Four months before, on the second floor, Giuseppe Verdi had died. In like manner, in our city, cylinders and discs were recorded by monologists, musicians and payadores.

Those cylinders for phonographs had a listening length of two minutes. This was until 1908 when they managed to extend it up to four minutes. And it remained without changes until 1929 when cylinders were no longer used. Up to that date cylinders and discs co-existed.

The early criollo discs appeared in 1902 and were played back in the novel gramophones which began to be sold in our country in 1900. These early discs which contained Argentine songs had a diameter of seven inches wide (in fact, they were between 170 and 185 mm wide) and the listening duration was between a minute-and-a-half to two minutes long. Then the payadores’ voices and the music bands began to be recorded.

I shall mention some performers and some pieces that were recorded in those small discs: “Dejá de jugar ché ché” (tango criollo) by Alfredo Munilla; “La ñatita” (triste) by Arturo De Nava; “Diana al general Mitre” by the Teatro San Martín orchestra; “Aparicio Saravia” (recitation) by Eugenio Gerardo López; “Sombra” (Dr. Leandro N. Alem’s poems) recited by Ángel Villoldo; “El pimpollo” (tango) by Ángel Villoldo; “Olvídame” (tango) by José María Silva; “Guido” (tango) by the Banda del Regimiento de Buenos Aires. All these recordings were cut into matrices in Germany, in Hannover and Berlin.

I shall mention some performers and some pieces that were recorded in those small discs: “Dejá de jugar ché ché” (tango criollo) by Alfredo Munilla; “La ñatita” (triste) by Arturo De Nava; “Diana al general Mitre” by the Teatro San Martín orchestra; “Aparicio Saravia” (recitation) by Eugenio Gerardo López; “Sombra” (Dr. Leandro N. Alem’s poems) recited by Ángel Villoldo; “El pimpollo” (tango) by Ángel Villoldo; “Olvídame” (tango) by José María Silva; “Guido” (tango) by the Banda del Regimiento de Buenos Aires. All these recordings were cut into matrices in Germany, in Hannover and Berlin.

Payadores made their appearance in cylinders in 1902 (Phrynnis). Many times by listening to them I have come back, with my imagination, through time in such a way that I managed to be alongside those primitive artists in 1902 at the precise time of the recording session. It was as if I were seeing how a helical groove or a spiral was etched on wax and as if I was sharing with them their thoughts, their illusions, their surprise to know that their singing and their instruments would be kept throughout time. But what they would surely not understand was that, nearly a century later, we would be the surprised ones.

That was a time when wealthy people enjoyed the marvelous talking machine and, among other things, the electric light brought by Edison’s lamp.

That was a time when wealthy people enjoyed the marvelous talking machine and, among other things, the electric light brought by Edison’s lamp.

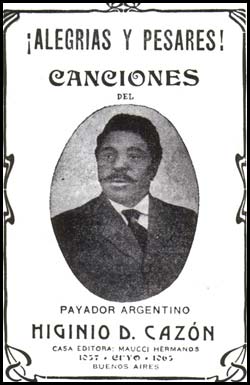

In our city in 1904, 10-inch (25 cm) discs labeled Zonophone were recorded and were pressed in Germany in 1905. The recordings included itinerant singers like Gabino Ezeiza, Higinio Cazón, José Madariaga, Arturo De Nava, Ángel Villoldo and singers like Andrée Vivianne (the first Franco-Argentine woman that recorded tangos on cylinders in Buenos Aires) and orchestras like the one of the Teatro Apolo and also the Police Band led by maestro José María Rizzuti. Thanks to them and many others more we today are able to get acquainted with voices and pieces that still are unknown to us.

Years before, talking to a good friend such as Rubén Pesce, I recall he told me: «These cylinders and discs contain excerpts of music and singing of those who were forerunners of our criollo heritage and many of the non-published pieces appear in the catalogues and programs of the circuses and theaters of the period and have become then, the last existing document».

I cannot omit the name of a foreseer, Carl Lindströn, that in Germany where he was based, at the turn of the last century he made out what recorded music and voices would mean for future generations.

Many payadores were forever attached to our memories by means of the discs produced by Lidströn in Germany. The recordings were made in Buenos Aires and were in charge of the local dealers. At this early period, the peak is in 1908 and 1909, there is a great enthusiasm in the population that request for a larger number of performers. The record dealers had the chance to offer wider catalogues for their customers and to encourage the sale of gramophones. The reason for the people’s enthusiasm was based on the preparations for the celebration of the nation’s centennial in 1910. As an example, here is an anecdote that Manuel Flores, Celedonio Flores’ brother, told me when he was very old: «When I was a young kid I lived in Villa Crespo on Loyola Street and on May 25, 1910, together with some other young neighbors, we walked to Plaza de Mayo carrying an Argentine flag. At the beginning we were less than fifteen. We walked along Rivadavia street and as long as we were walking people were increasing our group until the time we were near the square the column was four blocks long».

Many payadores were forever attached to our memories by means of the discs produced by Lidströn in Germany. The recordings were made in Buenos Aires and were in charge of the local dealers. At this early period, the peak is in 1908 and 1909, there is a great enthusiasm in the population that request for a larger number of performers. The record dealers had the chance to offer wider catalogues for their customers and to encourage the sale of gramophones. The reason for the people’s enthusiasm was based on the preparations for the celebration of the nation’s centennial in 1910. As an example, here is an anecdote that Manuel Flores, Celedonio Flores’ brother, told me when he was very old: «When I was a young kid I lived in Villa Crespo on Loyola Street and on May 25, 1910, together with some other young neighbors, we walked to Plaza de Mayo carrying an Argentine flag. At the beginning we were less than fifteen. We walked along Rivadavia street and as long as we were walking people were increasing our group until the time we were near the square the column was four blocks long».

In those discs, the payadores with their singing fervently showed their infinite love for the fatherland because the circumstances they underwent were and will be ours. Furthermore, historically, they helped us to grow up. Unlike the learned great writers, payadores were rudimentary and some of them scarcely know how to read or write. However, their instinct was such that with a limited language they were capable of touching the people’s heart. Frequently, with some simple improvised quatrains they brought universal knowledge. Towards the latter part of the nineteenth century illiteracy in our country was high and, unknowingly, payadores like also singers, actors, musicians, monologists, comedians and popular poets, through disc and gramophone contributed to low it down in a few years.

To be aware of sound contents expressed in a disc it was not necessary to know how to read or write. Consequently, those phono-mechanical machines spurred young and adults, influenced them to learn, drove them to the field of study, provoking an approach to school. Not only in our country this happened, but also in the whole world and many were the enterprises that as from 1900 sold cylinders and discs for language learning.

I think that this first sound document of genuine Argentina origin that I have dedicated to the early payadores that had the courage to commit their singing to the «talking machines» will help young researchers and scholars to get closer to the origin of the interpretive genre. If it fulfills that objective my satisfaction will be complete.

Eugenio Gerardo López, the first to write and spread a commercial jingle and also an exceptional monologist, renamed phonographs and gramophones as «talking machines». In 1902 the Edison house released a cylinder entitled “El gaucho y el fonógrafo”. In 1906 he again released the jingle with some modification, this time for a Victor Record disc and was entitled “El gaucho y el gramófono”.

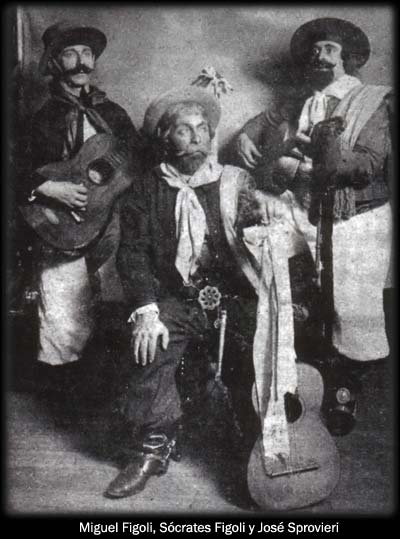

Lastly, it is worthwhile mentioning some other payadores: Sócrates Figoli, José Sprovieri, Arturo Mathón, Nemesio Trejo, Generoso D'Amato, Aída Reina, Pancho Cuevas, Francisco Bianco’s sobriquet, Antonio Caggiano, José Betinotti, Juan Pedro López, Miguel Figoli, Ambrosio Río, Nemesio Constantino, Ramón Vieytes, Florio Silva, Ángel Greco and Evaristo Barrios, among many others.